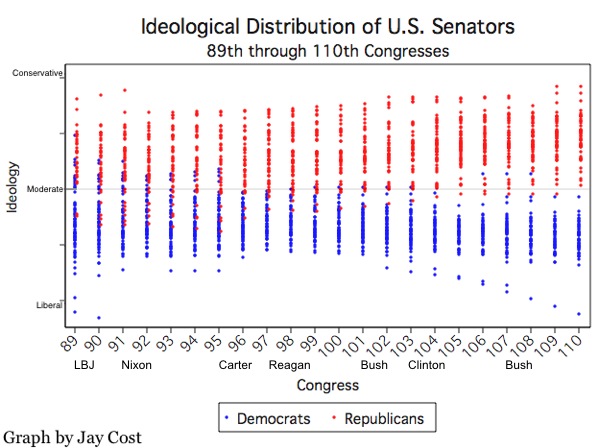

In today's Senate, 55 votes isn't enough to "win," or anything close to it; it's enough to get you five votes away from the 60 votes you need to shut down a filibuster. Only then, in most cases, can a law be passed. The modern Senate is a radically different institution than the Senate of the 1960s, and the dysfunction exhibited in its debate over health care -- the absence of bipartisanship, the use of the filibuster to obstruct progress rather than protect debate, the ability of any given senator to hold the bill hostage to his or her demands -- has convinced many, both inside and outside the chamber, that it needs to be fixed.Not so fast, says Jay Cost of Real Clear Politics. While Klein thinks that the Senate is "broken," Cost thinks the Senate is working just fine. The problem is that the two Senate parties have grown farther apart over the last 40 years. He explains by using the following graph:

He then goes on to explain:

Three important trends are evident from this picture. First, the party extremes have grown farther apart. Second, there are now fewer genuine moderates in the United States Senate than at any point in the last half century. Third, there used to be a sizeable ideological overlap between the two parties in the Senate. It no longer exists. Put simply, the Senate parties have become ideologically polarized.Cost goes on to explain that removing this tool would make the upper chamber a more chaotic place. The majority party would only have to convince 51 rather than 60 Senators and they would pass more partisan legislation because there would be no check to moderate legislation. Also Cost notes that this would make for unstable policy coming from Washington. Legislation passed when one party is in power would be rescinded when the other party comes to power. Cost notes:

This helps explain the increasing use of the filibuster. As the parties drift apart ideologically, the majority party will more likely introduce legislation that the minority party can't accept, giving the latter a stronger incentive to block it via the filibuster. Using the filibuster is thus a rational response when one finds oneself in the smaller half of a polarized chamber, which is more likely to be the case today than 45 years ago.

If nothing more than a simple majority is necessary for sweeping changes, what stops a newly victorious party from undoing all the reforms implemented by the old majority, and instituting its own set of big changes? What would be the long-term consequences of that? If every biennial or quadrennial election brought the prospect of big changes in public policy - how could we practically plan for the future? We all expect things in 2013 to be generally the same as things in 2009. Eliminate the filibuster, empower a bare majority to impose ideologically extreme policies, and that expectation could become unreasonable.If you are still reading this post, you can probably guess that I am in favor of keeping the filibuster. As Cost notes, moderates are becoming less and less rare in the Senate, and Congress as a whole. It was the moderates that were the dealmakers that could get legislation passed. A bill proposed by the Democrats would have some Republican support and visa versa. But as the parties become more polarized, it only makes sense that when one party proposes a bill, the other party will oppose it. It also means that the party in power is really in power and the filibuster is the only tool the losing party has.

Klein and others are mad that there had to be so much work done to get 60 votes for health care to pass. If there were no filibuster then a health care reform bill would pass, probably with a public option. The remaining moderates in the Democratic party would be sidelined, and the liberal base would become even more powerful. That would be music to Klein's ears, but I think it would be bad in the long run for American democracy.

Part of the problem with our polarized climate today is that when one party wins an election, party stalwarts tend to think this is a mandate from the people to get their own agendas done. They also think that a losing party basically has to sit there and take it. So, in the health care debate, Democrats think that all Republicans should basically shut up since they won the election.

But this isn't a pure democracy, it's a republic that believes that even minorities have to be listened to. People may not like that the GOP was threatening to use the filibuster, but is the only voice the GOP had. The same goes for when the Democrats were the minority party. They need to be able to have some say in how a bill is crafted and absent bridge building moderates, this is how minorities can speak.

Too the winner goes the spoils might work in sports, but not in politics.

No comments:

Post a Comment